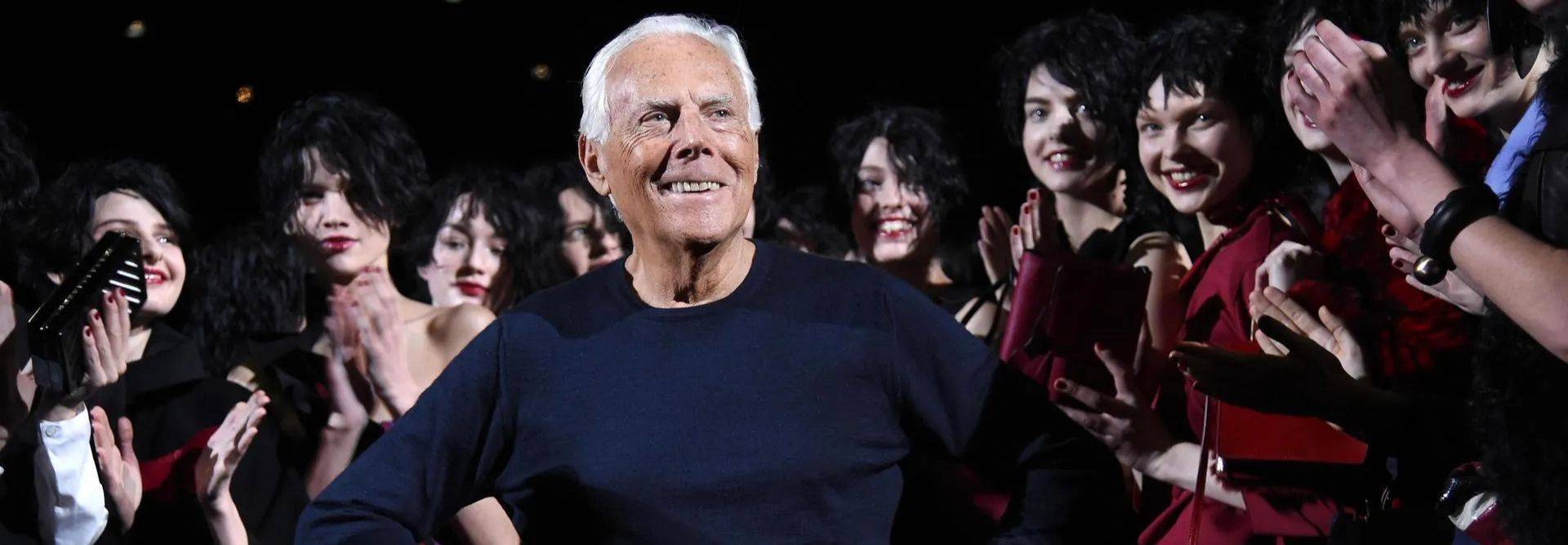

Giorgio Armani, the king of fashion who revolutionised with elegance

Giorgio Armani (1934-2025)

Article written by Ana Llorente, Lecturer in Fashion at UDIT, University of Design, Innovation and Technology and PhD in Fashion History.

Few have held the crown in fashion, and he did so not only by adapting his values to new commitments for the industry's agenda, but also as a representative of "Made in Italy", through the aesthetics of sobriety, asceticism, purity of lines, harmony of forms and idealised naturalism. A participant and representative in the early 1980s of one of the forms of expression of power dressing, the success of the Piacenza designer's designs was based on the transfer of traditional Neapolitan tailoring techniques such as softening the surfaces of men's suits by stripping them of the rigidity of their shoulder pads and linings, while at the same time hardening those of women's suits through uniforms that were worn on the bodies of the female executives who were populating the top echelons of the business world. This language seems to be the result of a very particular educational and professional background with which he may have developed a special instinct for understanding bodies, materials and human needs. He did not study fashion or art. Armani was a doctor by training and, after a period in the army, he worked for a pioneering and advanced department store, La Rinascente, where he trained his knowledge of fabrics, contact with customers and the creative vision to satisfy them. He started, therefore, from a rooftop and, far from bringing the house down, it gave him a bird's eye view of fashion. So much instinct that, when Nino Cerruti, before hiring him, put him to the test by placing different fabrics before him and asked him to choose the ones he liked best, Giorgio took the same ones that the stylist liked.

Since the seventies, he detected the need to offer a sensual androgyny in women's fashion. A sense of comfort based not so much on his use of soft fabrics, but on the feeling of security provided by outfits that allowed her to mimic and compete in the spheres controlled by men. He also made use of a purification of designs, devoid of superfluous details, which later sailed against the paroxysm of consumerism in the eighties. It also advocated, probably aided by vertical branding, a contemporary sense of quiet luxury intrinsically linked to the purity and harmony of any classic style. Classicism is a key term for the cultural interpretation of a man who, although dubbed by the media as "Re Giorgio" (King Giorgio), has in fact held an empire. That of women's fashion, but also of men's fashion, whose more contemporary history is partly written in Italian thanks to Armani. He even changed the way men's suits were made, a sector that had been stagnant since the Men's Renunciation of the 19th century. The Armani man has moved from the 1970s through periods of sensuality, sophistication and perfection in which he controlled men's clothing, to the humility and bohemian casualness of the 2000s.

He loved cinema and wished he had been a director, as he confessed to Martin Scorsese in the 1990 documentary, Made in Milan. Although he never fulfilled his frustrated vocation, he managed to dress stars such as Lauren Hutton, Michelle Pfeiffer or a Jodie Foster who, in 1992, received not only an Oscar in an evening gown and satin gloves by Armani, but the mention of one of the best dressed women in the world thanks to the Milanese outfit. If the evening gown was a key typology in shaping the history of Armani, the red carpet was the stage for her international projection. His name, often linked to Scorsese's films, is written in the history of film costumes with examples ranging from American Gigolo (dir. Paul Schrader, 1980), One of Us (dir. Martin Scorsese, 1990) or The Untouchables of Eliot Ness (Brian de Palma, 1987) to The Wolf of Wall Street (Martin Scorsese, 2013) or Belly of an Architect (dir. Peter Greenaway, 1987). It was not for nothing that in the late 1980s, Armani became the European firm with the highest sales in the United States.

Curiously, architecture has become one of the facets most closely linked to his career; from the iron control over the design of his boutiques or, for example, the Armani Hotels, to his affection for the work of Tadao Ando. Not in vain, since 2001, when the Japanese designer designed the Armani/Theatre where a large number of fashion shows and events linked to the firm have been held, the collaboration between the two has been fruitful and logical due to the stylistic harmony between the fashion designer and the architect.

Beyond a company that, backed since 1978 with the signing of an agreement with the clothing company GFT, has reached a turnover of more than two and a half billion euros a year, Armani has conjured up an incomparable audacity. Who does not remember that he was the first to react in that month of February 2020 when, forced to cancel the invitations to his presentation at Milan Fashion Week with less than 24 hours' notice, he broadcast live a fashion show empty of attendees, but full of those present via the online medium? A discreet genius like his sense of elegance, since 1982, he has also conjured up the art system by being the protagonist of exhibitions, collective or monographic, which, although not without controversy for this field, such as the one that led in 2001 to the Thomas Krens scandal at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, have been essential for understanding fashion as culture. While waiting for the hour, we can savour a portion of his generous legacy at his Armani/Silos in Milan, which, until 28 December 2025 (and probably with an extension), will host the spectacular "Giorgio Armani Privé: 2005-2025. Vent' anni di Alta Moda".